American mystery writer James Lee Burke has been a favourite Scorpion Press author. For some years a new book would appear by Jim, each with the customary appreciation by an author of note. For the special edition of Swan Peak, publisher Michael Johnson wrote the appreciation. It appears here in full. A list of all the Burke books issued by the press is given at the end.

It is an obvious, if sometimes imperceptible fact that the novel must die in order to be re-born. Arguably, the difficult even trau matic period for the national psyche In the United States during the early 1970s to the mid ’80s – Presidential impeachment, post Vietnam anxiety and absence of moral leadership revealed in the ‘Pentagon Papers’, not forgetting the Iranian hostage crisis – left the American people and the American novel with few voices of note. There was not much that could be said when the country was itself stuck in a quagmire, unsure of its direction.

matic period for the national psyche In the United States during the early 1970s to the mid ’80s – Presidential impeachment, post Vietnam anxiety and absence of moral leadership revealed in the ‘Pentagon Papers’, not forgetting the Iranian hostage crisis – left the American people and the American novel with few voices of note. There was not much that could be said when the country was itself stuck in a quagmire, unsure of its direction.

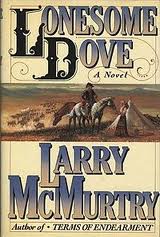

True, older literati such as Saul Bellow and Norman Mailer and the important writer of Vietnam angst, Robert Stone, were still producing valuable work; but it was in other more imminent popular genres where some redemption of the nation’s soul was to come about. Perhaps the most singular influences was the re-discovery of a realistic, inclusive and morally assertive series of Cowboy and Indian stories beginning with Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove (1985); from the same source of the Old West came the search for a sage-like wisdom of an older America derived from the open spaces, rivers, landscapes and peoples found in the Border Trilogy by Cormac McCarthy (1992 – 1998); and similarly the early 80s Indian holistic novels by Louise Erdrich.

The East coast literary elite had for generations derided and refused to publish indigenous American voices, particularly if they could be interpreted along lines of tolerating ethnicity or alternative visions of the past and possible futures. They preferred apolitical satire, quietist homespun tales and a cosseted view of social betterment through respectable channels. Thus the American Dream could be attained by all, but only the brightest and most privileged found satisfaction or could articulate the path.

However, after the Vietnam backlash with so many disproportionate fatalities and injuries among the black and backwoods boys, a less deferential, freer understanding of one’s place and self-identity grew stronger. Ethnicity and regionalism began to feature as a pathway out of the dominance of the metropolitan world-view. A few Black, Native American, and Latino voices began to gain acceptance with a new reading public, a growth assisted by this social awareness of ethnicity and other issues that had been hidden.

In summary, writers such as McMurtry were searching out a different way of looking at the past. It still had heroism and bravery – but it was now better equipped to give a message of mutual sharing of a wider cultural heritage, rather than that of an unmediated expansionist drive west, accompanied by too much interference born of superiority, and with it not enough restraint. It also touched on an earlier era when frontier’s people had a dynamic mixture of motivations and lived life to the full. They would have known of the betrayal of the Sioux by representatives of the U.S. government and suspected they might have been next to be pushed aside. Those feelings were echoed in the broadsides of the anti-government/anti-banker stance of the party of Jefferson, Jackson and Bryan; and later in protest at the ugly discontent of the Depression in the realism of Dos Passos, Dreiser and Steinbeck.

* * *

After three well received novels between 1965 and 1971, James Lee Burke’s efforts to develop as a writer were undone by an uneasy reception in New York. His next book, The Last Get-Back Boogie took another nine years before it was accepted – and only then by a college press. Burke had written ceaselessly and did side jobs in open spaces as a reporter, land surveyor and on a Texas oil pipeline – but publishers were uneasy about the author whose background and interests were unconventional. He came from the Deep South, and like many before him lamented the Rebels who died in vain when the Union was divided.

After three well received novels between 1965 and 1971, James Lee Burke’s efforts to develop as a writer were undone by an uneasy reception in New York. His next book, The Last Get-Back Boogie took another nine years before it was accepted – and only then by a college press. Burke had written ceaselessly and did side jobs in open spaces as a reporter, land surveyor and on a Texas oil pipeline – but publishers were uneasy about the author whose background and interests were unconventional. He came from the Deep South, and like many before him lamented the Rebels who died in vain when the Union was divided.

As an outsider, countryman and a practising Catholic, he was always going to be an unpalatable messenger for some. Under the influence of Charlie Willeford he made the transition to raw, penetrating mysteries. Why mysteries? The mystery thriller had been idling along for a decade or more. Rooted in the “pulps” it had become mildly respectable with the likes of Hollywood projecting its subject matter on the big screen. Nevertheless, with some exceptions the genre had not progressed; the settings and situations had become routine: attractive sultry woman and hard-to-the-core men, with someone scheming to outdo them all. For generations the noir had been set among the contradictions between the poor urban backstreets, and the wealthy suburbs – whether it mirrored LA or Boston – the narrative of gangsters, molls, misfits, innocent victims and society figures with a grudge was much the same. Except, of course, in the second half of the 20th century the big cities (and suburbs) all had a veneer of success and stability. This is why Chandler and his followers created an older, more romantic atmosphere for LA and California. This disposition toward recasting the past was a clue to Burke’s future as a writer.

James Lee Burke was a man with a vision. It was partly based on the idea that everyday living was in a sense a sacred duty, life was fulfilled in phy sical action and social interaction. Like Richard Ford and the late Ray Carver, he liked hunting and fishing and the old treasured ways. Having lived and worked in the southern part of Texas and Louisiana it was natural to set his detective stories in the Bayou country. It was not long before he added another setting of beauty, the rugged landscape of Montana. Discerning readers will know that this creates a modern facsimile of the settings found in the famous cattle drive from Texas to Montana described in the previously mentioned Lonesome Dove.

sical action and social interaction. Like Richard Ford and the late Ray Carver, he liked hunting and fishing and the old treasured ways. Having lived and worked in the southern part of Texas and Louisiana it was natural to set his detective stories in the Bayou country. It was not long before he added another setting of beauty, the rugged landscape of Montana. Discerning readers will know that this creates a modern facsimile of the settings found in the famous cattle drive from Texas to Montana described in the previously mentioned Lonesome Dove.

It is a great strength that Burke’s settings and characters are a little strange because they are not drawn from the Ivy League colleges, the clever double-talking lawyers or scam artists found in other popular thrillers and PI novels. Instead, almost everyone is flawed: from the central character, Detective Dave Robicheaux (recovering alcoholic) to his near anarchic partner Clete Purcell, and the salty female Sheriff Helen Soileau. Not to mention the long list of women that Robicheaux has loved and lost. The latest being ex-nun Molly. They are country folk, generally honest and to them are added the backcloth of a multitude of downtrodden humanity of various creeds and hues. Even the rapists and psychopaths have different sides to them. Nearly all of humanity in the Robicheaux series is in turns good and bad, saved and fallen; they are catching up with themselves, and the interest is often sustained through these complex interactions.

Dave and the others speak when necessary with a local dialect – giving an authentic feel. It is not obtrusive and blends with the sensuous character of the southern Louisiana setting and never seems trite or overdone – just natural. The occasional dialect  combines well with images of landscape, spicy food, jazzy music, and the bonds of friendship can conjure up a mellow atmosphere, which reminds me of Linda Ronstadt’s song “Blue Bayou”. This cultural texture has a kind of serenity, depth and sacredness by being of the landscape and having some regard for life in its majesty. Of course, this attractive feeling of contentment is hinted at and not all pervading. Quite simply, it is trampled by the layers of criminal subterfuge and wanton wrongdoing.

combines well with images of landscape, spicy food, jazzy music, and the bonds of friendship can conjure up a mellow atmosphere, which reminds me of Linda Ronstadt’s song “Blue Bayou”. This cultural texture has a kind of serenity, depth and sacredness by being of the landscape and having some regard for life in its majesty. Of course, this attractive feeling of contentment is hinted at and not all pervading. Quite simply, it is trampled by the layers of criminal subterfuge and wanton wrongdoing.

The crimes are for Burke, past, present and future with suspense employed to darken the feeling that something really bad is about to happen. The action comes fast and furious; violence is so being employed as the medium both to explore fiery social tensions and help resolve them afterwards. Burke is interested in the level of subconscious underneath. As a writer, this technique enables him to bring the reader in – to open up a channel inside ourselves to our conscience, as equally the real intention in the plotline is to allow time and certain encounters to begin the process of healing. More than this, the writer goes beyond the transient immediacy of what has recently occurred, however painful, to the greater pain of the generations that had gone before.

His main characters always have a past that informs the present; aside from freewill and self-determination, Burke’s keen interest is in the undercurrents, emotions forced together by hardship and resilience, or the long past forms that social relations took – forms of subservience, the hurts and feuds, as well as the stoic, clinging friendships, and not forgetting the altogether happier times.

Thus the past is dangerous, compromised and deadly, but may equally be the source of the brightest inspirations and memories. Somewhere along the way, it is all layered by specific human relations of class, wealth and status or simply other non-acquisitive priorities, pulling in other directions.

Burke knows that the Civil War was won and lost in the South-West where armies moved great distances and gained surprising victories. Both sides sustained heavy losses in the defence of the Confederate strongholds at Port Hudson and Vicksburg, which controlled the western river border. This was not far from the state capital, Baton Rouge. These events, together with the bloodbath at the Methodist chapel at Shiloh, near Savannah, still echoes through many of his books. This old past and our present are brought into nagging relief in such titles as Heaven’s Prisoners and In the Electric Mist with Confederate Dead. Some of the dialogue in these stories is with people who may or may not be dead. This is not necessarily a “stream of consciousness” technique – for as Catholics both Dave and his creator Jim view death as the door to another world. In moments of doubt, and sorrow Dave is entwined with those who have gone before. This experience occurs in the earliest and latest novels and shows the author’s connection to events such as Shiloh and his earnest desire to unburden his soul, to mitigate the shared loss.

Finally, it is notable that Jim’s fledgling literary career was feulled by the desire to express in written form his acute sensory experiences of the great outdoors he had found in his various paid jobs. These experiences became a kind of well deep into the caverns of natural and human landscape. When he transferred his literary efforts to writing detective fiction it did not initially achieve very much. Then the move to Little Brown and the Edgar book, Black Cherry Blues did his prospects the world of good. Editor Pat Mulch decided to “showcase a writer who’s been ‘under published’”. Jim found a willing and growing audience as he toured from state to state, giving readings for a month if not two. Readers got to know the man and his work. When I visited a store at Evanston, Illinois and ordered some signed copies of A Morning for Flamingoes I left a note because I had to return early to the UK. Later I received a postcard with a nice greeting and apologies. I was a complete stranger – yet he responded generously with his time and gracious comments.

Jim has always worked hard, and for his many fans he has been a dream of a writer and a fine human being. He came to the mystery genre at just the time when it began to open up with fresh new voices. He is however, the one the others acknowledge as doing most to help create a broader, invigorating and socially relevant reading public that supports the mystery market today.

God bless, Jim.

copyright Michael Johnson 2008

James Lee Burke books in the Scorpion Press series:

Sunset Limited 1998 appreciation by Michael Connelly

Crusader’s Cross 2005 appreciation by Robert S Reid

Pegasus Descending 2006 appreciation by James Sallis

Tin Roof Blow Down 2007 appreciation by Phil Rickman

Swan Peak 2008 appreciation by Michael Johnson

Rain Gods 2009 appreciation by Robert Crais

The Glass Rainbow 2010 appreciation by John Connolly

Feast Day of Fools 2011 appreciation by James W Hall

Creole Belle 2012 appreciation by Barry Maitland