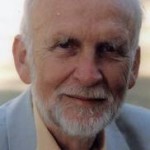

Michael Dibdin was a little underrated by the crime fiction fraternity because he was a bit of an outsider living much of the time abroad. As a person I liked him for his charm, easy humour and wit. I have to admit he was for me an enormously influential figure, as a crime writer and critic.

I first heard Michael speak to an audience at the Semana Negra crime writers’ convention in Northern Spain in 1994. It was immediately evident that he was an advocate for crime fiction not as a constricted form – but as a stimulating near revolutionary motif – being at one and the same time, entertainment and critique. It was his instinct to try to find a way into showing insights into the many levels of the ‘modern’ social structure – obviously multi-dimensional as political, economic, cultural etc. – and doing this through crime fiction in the sense of the roman noir, so popular in parts of Europe and Latin America offered this wider scope.

Dibdin then pointed to the modern crime novel as a form that was critical of a “taken for granted” acceptance of social norms, that was a mixture of classes, attitudes, and significantly said something about the power relations in society. Allied to his critical agenda he believed that ‘crime’ was not literature with a big ‘L’ but a form of popular expression which could potentially be both literature and a cultural force. In this idea he was influenced by the Italian Marxist Gramsci. His anthology, The Picador Book of Crime Writing demonstrated how diverse and challenging to the expectations of the genre writers could be if freed from from the rigidities placed on them by publishers and presumably those that gave guidance on what was acceptable.

For many though Michael Dibdin will be remembered for the series of books with complex character, Commissioner Aurelio Zen who was an inspector in a criminal investigation department of the Ministry of the Interior. In the first few novels Zen was a mystery figure – an artifice or cipher to enable the plot to move in different directions; but Zen became an engaging character that his readers waited to see how he would respond. But the Zen books are really about the different characters in different regions of Italy. Michael was ready to tell us about the Mafioso in Sardinia as he was about high-status families in Turin or Florence.

For many though Michael Dibdin will be remembered for the series of books with complex character, Commissioner Aurelio Zen who was an inspector in a criminal investigation department of the Ministry of the Interior. In the first few novels Zen was a mystery figure – an artifice or cipher to enable the plot to move in different directions; but Zen became an engaging character that his readers waited to see how he would respond. But the Zen books are really about the different characters in different regions of Italy. Michael was ready to tell us about the Mafioso in Sardinia as he was about high-status families in Turin or Florence.

Michael was a great admirer of Ruth Rendell and what she achieved in pushing the boundaries of detective fiction. I think he enjoyed her books because she was like him was a superb plotter, and you never knew where a Rendell book would take you. Knowing his admiration I asked him if he would care to write an appreciation. Unfortunately, he replied that he did not write about living writers.