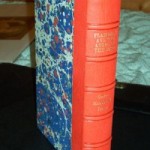

Barbara Vine, Asta’s Book deluxe lettered

£180.00

Deluxe copy 1/20 only. Writing as Barbara Vine Ruth Rendell has published 15 of the most outstanding multi-layered crime novels of the last 25 years. They are read and re-read for the pleasure they give. This is one of her best with an appreciation by her champion the late Julian Symons.

In Stock: 1 available

Barbara Vine is t

Barbara Vine is t he alter ego of the prolific and gifted crime writer Ruth Rendell Having pushed the boundaries of the police procedural with her Wexford books and produced a string of sexgrills and psychological thrillers, she felt the need to move into new territory with books that offered rich and intriguing character studies and had detailed background research. Rendell had already charted the path with novels of urban alienation and suburban dysfunctionally – the Vine books allowed her space to expose this as cemented in sex and class divisions and to build a more informative backdrop – well beyond the classical detective formulae.

he alter ego of the prolific and gifted crime writer Ruth Rendell Having pushed the boundaries of the police procedural with her Wexford books and produced a string of sexgrills and psychological thrillers, she felt the need to move into new territory with books that offered rich and intriguing character studies and had detailed background research. Rendell had already charted the path with novels of urban alienation and suburban dysfunctionally – the Vine books allowed her space to expose this as cemented in sex and class divisions and to build a more informative backdrop – well beyond the classical detective formulae.

The esteemed crime critic, writer and past President of the Detection Club, Julian Symons had long advocated that Ruth Rendell was in range and power the novelist of her time. In his appreciation he speculates as to the reasons she adopted the pseudonym and gives a loving account of her best books. He says that he is reminded of Wilkie Collins and in Asta’s Book we have a murder mystery buried in the past. Susan Rowland, an expert on detective fiction called it an “extraordinary Vine novel” and noted that Ruth Rendell/Barbara Vine “turns detective fiction into a socially progressive form” by making restorative justice a “future orientated desire, not the society of now or the past”. These comments are from British Crime Writing: an encyclopedia edited by Barry Forshaw. Forshaw himself, another highly experienced aficionado of crime noted that: “Asta’s Book is a study in betrayal, personal identity, and of course, murder. Like all the Vine novels … this is psychological crime writing of the most fastidious kind, always idiosyncratic in its treatment of character”. (from the Rough Guide to Crime Fiction).

Plot summary: 1905. Asta and her husband Rasmus have come to east London from Denmark with their two sons. With Rasmus constantly away on business, Asta keeps loneliness and isolation at bay by writing her diary. These diaries, published over seventy years later, reveal themselves to be more than a mere journal, for they seem to hold the key to an unsolved murder, to the quest for a missing child and to the enigma surrounding Asta’s daughter, Swanny. It falls to Asta’s granddaughter Ann to unearth the buried secrets of nearly a century before. From the 1994 Penguin paperback edition

The Scorpion Press edition comprised 99 numbered and signed copies. The copy is one of the few deluxe lettered state, one of 20 with five raised bands and issued privately. It is signed by Ruth Rendell and Julian Symons. A rare collectible.

George MacDonald Fraser, Flashman and the Angel of the Lord

George MacDonald Fraser, Flashman and the Angel of the Lord

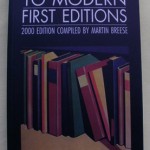

Breese (edited): Breese’s Guide to Modern First Editions (2000 edition)

Breese (edited): Breese’s Guide to Modern First Editions (2000 edition)

Rating by “The Independant”, London on April 10, 2012 :

“For her new novel, Barbara Vine, who is partly Danish as well as being partly Ruth Rendell, has put Danish characters in an east London setting, adding cultural and historical richness to an already complex narrative. The eponymous Book is a diary, started in 1905 and spanning 62 years, written by a Danish woman who has come to live in Hackney with her husband and two small sons. Asta is 25 when the diary begins and pregnant with, she hopes, a longed-for daughter. Years later, after Asta’s death, the journal has become famous as a sort of Urban Diary of a Edwardian Lady, and Swanny, daughter, translator and keeper of her mother’s flame, is a cult figure.

When Swanny also dies, her niece, Asta’s granddaughter Ann Eastbrook, inherits the diaries, and it is Ann’s perusal of them that reveals significant gaps. She marks a passing reference to a Lizzie Roper who lived near Asta. Coincidentally, an old enemy of Ann’s, a woman who ‘stole my lover from me and married him’, is working on a documentary film about the unsolved murder, in 1905, of Lizzie Roper, and the disappearance of her infant daughter. (Lizzie Roper’s mother was killed at the same time, but she was an old harridan and so nobody cared very much.)

The plot thickens, as only a Barbara Vine plot can: is it possible that Swanny was not really Asta’s daughter, but the abducted child of Lizzie Roper? After all, in her old age, Swanny’s personality underwent a disturbing split, and from time to time the svelte literary icon would lapse into a shuffling slattern with a penchant for knitting ‘somethink’ in lilac wool. Was Swanny reverting to type, or was it just senile dementia? Or might Swanny have been the daughter of Asta’s long-suffering servant, Hansine?

Like all Barbara Vine’s work, the novel is meticulously researched. You can check the route taken by the suspected murderer, Lizzie’s husband, and indeed all the locations, in an A-Z; you can feel the summer heat rising from the pavements, breathe the stuffy air of claustrophobic rooms, and smell the sweaty, stifling clothes. Vine excels at describing houses, and makes them as sinister, as much part of the action, of any of her characters; there is The House of Stairs itself, and Ecalpemos in A Fatal Inversion, and here we have the ordinary-sounding Devon Villa, where the murdered Lizzie Roper and her mother lie undiscovered for days, and the disappearing child, a recurrent Vine/Rendell preoccupation, makes her last, laborious ascent of the long staircase. Even the large doll’s house built by Asta’s husband gives a telling cameo performance.

This is an engrossing double-detective story, a mixture of biography, true crime and romance peopled with vivid minor players and red with herrings. Asta herself is a bit of a cold fish; her diaries generate no warmth, even when she writes of her love for her children or a late, unconsummated, love affair, and that makes their popular success, for all their period detail set against the background of world events, a little hard to understand. The tone of her first person singular militates against her as much as her own actions do: we can feel some sympathy for her in her exile with a husband often away on business, but even she acknowledges that she lacks ‘niceness’.

Still, one doesn’t look for niceness in Barbara Vine characters: mystery, suspense and a consuming plot are all provided, and while there are thematic threads running through her work, Vine reinvents herself as a novelist every time”. Published in “The Independent”, 28 March 1993

Rating by Julian Symons on May 21, 2012 :

Extract from the Appreciation by Julian Symons

“Ruth Rendell is three fine writers, but the best of them is Barbara Vine.

That sentence will need no explanation for true Rendellites or Vineolators, but an elaboration of the way Barbara Vine came into being, and a personal guess at the reasons for it, may be of interest. Her first published book, From Doon With Death, introduced Chief Inspector Reg Wexford and his puritanical sidekick Mike Burden. The Wexford stories were written, the first of them, at a time when she thought straightforward detective stories with a central character were the only things she could get published. Yet almost from the beginning she wrote other books, tales for which any label seems inadequate, psychologigal thrillers that explored more and more deeply crimes springing from some sexual or social obsession that was often traced back to mistreatment or misfortune in childhood. The intricacies of parent-child relationships have always been an important element in her work. With these two strings to the Rendell bow, the Wexford police novels and the more disturbing horror stories and sexgrills, what need was there for a third?

Why was Barbara Vine born in 1986 with A Dark-Adapted Eye, a novel that made no pretense at concealment, the wrapper saying flatly that ‘Barbara Vine is Ruth Rendell’? Ruth’s own explanation is that she had been trying unsuccessfully for several years to write a novel set in World War I, but eventually completed it with the period changed to World War II although part of the book was still placed back in time. For these reasons she thought it was ‘unsuitable as a Ruth Rendell’. Without questioning the explanation I think it is possible to suggest something more. Ruth Rendell is a finely ambitious writer, and I believe she felt in herself capacities for writing novels different in kind from the Wexford books and studies in psychology, and much wider in their range. It is true also that she takes crime stories seriously and may have been irked, as others have been, that they were for a long time treated simply as genre works marked ‘for entertainment only’. I think she wanted to show that the invisible line marking them off as inferior articles could be crossed. And since the best of her work is intensly personal, bodying out imaginatively her constant presentiment of some unnamable disaster or affliction, it may be she found it easier to express such feelings through the Barbara Vine books than in her other work”.