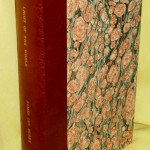

Ian Rankin, Doors Open

£68.00

£62.56

8% off!

Ian Rankin’s creation, Inspector John Rebus is a popular hero that transcends the stereotypical detective figure. Rankin uses the form to fill out a rounded character, a sense of place and the wider social reality. The is a standalone thriller, post Rebus and more in common with Lawrence Block’s Bernie Rhodenbarr than some of the darker British noir school. This edition contains an appreciation by the Scottish crime writer Denise Mina.

In Stock: 4 available

Ian Rankin‘s Inspector John Rebus is probably the best known contemporary British detective series apart from Morse. The first Rebus novel, Knots and Crosses (1987) was originally conceived as a one-off, and was followed by two non-series book before the second installment arrived in 1991. In the early 90s Ian Rankin was little known and although his thrillers showed promise he lacked a market for them. This changed when he decided to work on a book twice the usual length with multiple story lines, a back story rich in Scottish heritage, with overlapping contemporary concerns. Black and Blue (1997) was critically acclaimed, received the Crime Writers’ Association Gold Dagger and created the confidence and space for Rankin to develop and take the Rebus series to new levels; bringing significantly added zest to the growing book trade interest in a detective that was more about shadows and contradictions than solutions – thus noir came out of the shadows. This is his first standalone thriller post Rebus.

Ian Rankin‘s Inspector John Rebus is probably the best known contemporary British detective series apart from Morse. The first Rebus novel, Knots and Crosses (1987) was originally conceived as a one-off, and was followed by two non-series book before the second installment arrived in 1991. In the early 90s Ian Rankin was little known and although his thrillers showed promise he lacked a market for them. This changed when he decided to work on a book twice the usual length with multiple story lines, a back story rich in Scottish heritage, with overlapping contemporary concerns. Black and Blue (1997) was critically acclaimed, received the Crime Writers’ Association Gold Dagger and created the confidence and space for Rankin to develop and take the Rebus series to new levels; bringing significantly added zest to the growing book trade interest in a detective that was more about shadows and contradictions than solutions – thus noir came out of the shadows. This is his first standalone thriller post Rebus.

The combination of the seedy side of Edinburgh with the hand-drinking, tough but vulnerable policeman with humanity, and deft narratives paced like adventure stories was noted by television producers. Once the right leading man was found Rebus on the small screen came to rival other detective adaptations such as Wexford, Resnick and Morse.

Plotline from the Ian Rankin site: For the right man, all doors are open… Mike Mackenzie is a self-made man with too much time on his hands and a bit of the devil in his soul. He is looking for something to liven up the days and perhaps give new meaning to his existence. A chance encounter at an art auction offers him the opportunity to do just that as he settles on a plot to commit a ‘perfect crime’. He intends to rip-off one of the most high-profile targets in the capital – the National Gallery of Scotland. So, together with two close friends from the art world, he devises a plan to a lift some of the most valuable artwork around. But of course, the real trick is to rob the place for all its worth whilst persuading the world that no crime was ever committed. But soon after he enters the dark waters of the criminal underworld he realises that it’s very easy to drown…

The Scorpion Press edition was issued in 2008 with a run of 80 numbered and signed copies with an Appreciation by Scottish crime writer Denise Mina. She explores Rankin’s skill as a writer and his relationship with the reader. “For me”, she says, “its the situatedness that really sets his work apart and above. The characters are people we know now, the place, the coffee bars, the ancient city is the city of now so that the story is happening around the corner, the scam being plotted in the next booth in a bar, and the weather is outside your window right now. The attention to the details of what is happening around us, of social nuances and shifts, is a central element in the intimacy and and immediacy of his writing”. Doors Open has been made into a television film with Stephen Fry and is due to be shown later in 2012.

Carol O’Connell, Flight of the Stone Angel

Carol O’Connell, Flight of the Stone Angel

James Lee Burke, Light of the World

James Lee Burke, Light of the World

Rating by Stuart Kelly, The Scotsman on May 27, 2012 :

“FOR all those eager fans wondering what Rebus did next, after his retirement in Exit Music, a word of warning: Doors Open, Ian Rankin’s new novel, won’t tell you. There is a sly little wink when DI Ransome asks DI Hendricks how things are at Gayfield Square and gets the gruff reply, “A damn sight quieter since you-know-who retired.” But even without his most famous creation Rankin delivers a rattling, smart yarn. In a way, I’m disappointed I didn’t read this with a stinking cold, as Rankin is the bookish equivalent of a strong hot toddy; undemanding, invigorating and with a hefty, acid kick.

Doors Open was substantially written before Exit Music, and appeared as the Sunday Serial in the New York Times in 2007 – indeed, Rankin was the first British writer to be awarded the accolade, which he shares with such luminaries as Patricia Cornwell, Elmore Leonard and Michael Chabon. Revised and expanded for UK publication, it is equally familiar and unexpected.

Instead of the protagonist being a policeman, in Doors Open the central characters are wannabe criminals. Mike Mackenzie, a bored and wealthy software mogul, Allan Cruikshank, a financial adviser tired of being a grey man, and an irascible art professor, Robert Gissing, on the eve of his retirement from Edinburgh College of Art, cook up a scheme to “liberate” various paintings from the National Collection’s “overspill” warehouse in Granton.

They are all art-lovers, and are all suffering from anomie. Gissing resents the fact that great works are kept hidden away, Cruikshank wants a masterpiece of his own to give him emotional purchase over his philistine clients, and Mackenzie hankers after a portrait that reminds him of an attractive auctioneer, and some excitement. But pulling off the robbery slowly embroils them in a far seedier world. Their idea is to replace the paintings with fakes, so they recruit a chip-on-the-shoulder art student called Westie, who specialises in reproductions with hidden anachronisms (a plastic bag in the corner of a Constable, a black eye on the Skating Minister). They also need muscle, replica guns, a getaway van – and fortuitously, Mackenzie has run into an old school acquaintance, Edinburgh gangster Chib Calloway. . .

Doors Open has more in common with Lawrence Block’s Bernie Rhodenbarr novels or Donald Westlake’s John Dortmunder series, and Rankin name-drops both Ocean’s Eleven and The Lavender Hill Mob. The balance between comedy and “real” crime is held fairly well, and the ending satisfies well enough – although I had just an inkling that Rankin was holding back, and striving to unite the Rebus-style “justice” ending with his more radically amoral cast. …

Perhaps it’s a fossil remnant of the serial form, but some of the cadenzas on Edinburgh – the differences between the Old Town and the New, a mention of Jekyll and Hyde, the Trainspotting Tour in gentrified Leith – would probably appeal more to a first-time Rankin reader. Edinburgh, in a way, is the real villain of the piece – a city so small that no one can play six degrees of separation. In how quickly a network of coincidences, meetings and acquaintances can be uncovered, it’s closer to the St Mary Mead of Miss Marple than the sprawling metropolises of Ellroy, Lee Burke or McBain.

But none of that detracts from the pleasure of the novel. Rankin’s virtues of pace, cynicism, detail and neat plotting get the added benefit of some sharp humour and sardonic social observation. It can only whet the appetite for what Rankin really does next.

Stuart Kelly, “The Scotsman”