It came to my attention earlier this year that one of the most prolific and respected authors of crime fiction books has passed away. Reginald Hill was one of a select number of erudite and especially knowledgeable crime writers that grew up with a fondness for tales of adventure and folklore as well as the classic crime and detection stories; having distilled them as a youngster and later what is called the Great Tradition of English Literature he set about bringing intelligence and new energy to the British crime scene from about the 1970s.

It came to my attention earlier this year that one of the most prolific and respected authors of crime fiction books has passed away. Reginald Hill was one of a select number of erudite and especially knowledgeable crime writers that grew up with a fondness for tales of adventure and folklore as well as the classic crime and detection stories; having distilled them as a youngster and later what is called the Great Tradition of English Literature he set about bringing intelligence and new energy to the British crime scene from about the 1970s.

I have a particular fondness for Reginald Hill. He was especially well-liked and admired by those involved in the ‘business’ of publishing and the crime-writing community. His editor at Collins, Elizabeth Walter said that his first novel was extremely well written. She was his editor through his blossoming as a writer and I remember that her successor Julia Wisdom would tell me when asked if the latest novel was good, that it was likely to be short listed for an award. Hill was that good.

Reginald Hill was a northerner and after attending Oxford where he read English he taught at a school in Essex before moving to a Further Education College in Leeds, Yorkshire. When he set out to become a crime novelist with A Clubbable Woman (1970) Hill brought an ambition to do three significant things in this and his subsequent work: to re-work Falstaff and Prince Hal in his detective duo of Dalziel and Pascoe; to open up a commentary on the state of the social affairs in the country, in particular in northern England and on cause of feminism; and thirdly, if that were not sufficient, to devise new perimeters for the detective/crime format by drawing on broader literary devises and forms. Over the course of more than forty brilliant years Reginald Hill became the male British crime writer that the others pointed too for the high level of skill, consistency and dazzling experimentation which he brought to crime fiction.

Much has been written about Dalziel and Pascoe: what they represent and what they tell us about the changing world around us. Similarly, Pascoe’s wife Ellie tells us much about the changing role of women; while the homosexual Sergeant Wield allows us into another area of equality and changing social perceptions. The latter books in the series explore the limits of crime fiction. The BBC bought the rights to Dalziel and Pascoe and twelve series were shown between 1996 and 2007.

When we look back on the Dalziel and Pascoe series we find no simplistic formulae, but an evolving combination of relationships: some readers prefer the educated and sensitive Peter Pascoe, others either admirer or cringe at the antics Fat Andy, still others believe that Ellie Pascoe (nee Soper) is the driver of the plots with her feminine insight. Yet we must not forget the gay sergeant Wieldy. They all at times play important parts in the stories. My fondness stems partly from the seamless manner he balances these players on the stage, and partly from the intricate plots. Plots that have a touch of wisdom and earthiness.

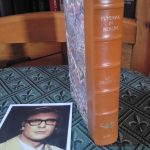

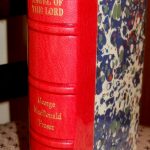

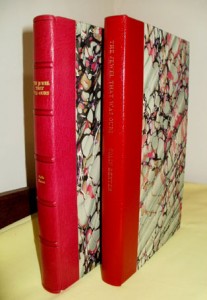

He was always courteous and extremely kind to me and Scorpion Press. He took an interest in our development and over the course of twenty years we corresponded from time to time. He made nine appearances with short stories for the two Detection Club collections, the Bouchercon collection No Alibi, an appreciation of Val McDermid and the four Dalziel and Pascoe novels (1992 – 1998). His most recent signed limited with Scorpion Press was just last year in the Crime Writers’ Association anthology, Original Sins.

At crime writer gatherings one always received a positive comment when his name came up in conversation. For me I found it pleasing that we achieved an international gathering of crime writers to do appreciations for the Dalziel and Pascoe volumes in the series: ex-pat Eric Wright who is a virtual Canadian (whom I met at Semana Negra in Spain), American mystery writer Walter Satterthwait, Yorkshireman John Baker, and finally the prolific English crime master Peter Lovesey.