I once met Edna O’Brien. It was a fine day at a signing in the Kensington High Street, not far from her London home. I remember her hair pushed up, the shining eyes and the deep textured voice. That was over 25 years ago. She is in the news just now with an autobiography and not so long ago with a new short story collection. Why Edna and her characters interest me is that through living boldly, pushing against boundaries, she and her fictional characters protrude along dimensions that speak to our world. She has a way of peeling layers of truth about her country, her native Ireland, that is not accepting but questioning; yet she is no mere critic of her peoples nature from the outside, for she carries something of the goodness of old Ireland, perhaps from the roots of its distant past.

I once met Edna O’Brien. It was a fine day at a signing in the Kensington High Street, not far from her London home. I remember her hair pushed up, the shining eyes and the deep textured voice. That was over 25 years ago. She is in the news just now with an autobiography and not so long ago with a new short story collection. Why Edna and her characters interest me is that through living boldly, pushing against boundaries, she and her fictional characters protrude along dimensions that speak to our world. She has a way of peeling layers of truth about her country, her native Ireland, that is not accepting but questioning; yet she is no mere critic of her peoples nature from the outside, for she carries something of the goodness of old Ireland, perhaps from the roots of its distant past.

We tend to forget that the modern crime novel only came into its own with much struggle with the dominant form of detection writing. In the form known as detective fiction the focal point was the puzzle and or the mystery, where the detective led the narrative story. It was not until writers such as Ruth Rendell and P D James began to establish themselves that the focus moved away from detection to the telling of the causes of crime and the motivation of character. Other more recent writers point to the influence of supposedly more penetrating practitioners from abroad such as Henning Mankell or Kathy Reichs, and the literary historians among us might look across the channel to George Simeon or across the Atlantic to Chandler or the pulp writers. All of them have some kind of critique of society and a moral centre. The birth of the modern from the old involved some pushing and jostling by critics and writers, some are no longer with us like Julian Symons; but I have a sense that the key break – still being marked out – is what might be called a social awareness, that people and society is multi-dimensional.

Certainly, some of that multi-type of social awareness is be found in the crime novels of Messrs Mankell and Reiches, and the more recent recruits to the genre. But the interesting point is that Henning and Kathy have been writing since the 1990s. They were championed by publishers and editors since they pitched for realism in crime. Others can credibly argue that Ruth Rendell’s sexgrills and psycho studies began the process of more realism and a peak into social ills a little earlier in the mid 1970s and blossomed into the massively influential Barbara Vines of the mid 80s. The other important contributor P D James really began to expand her scope at a roughly the same time, especially with A Taste for Death (1986). But if we look further back, outside the then puzzle-orientated and constricting form of the police procedural or its earlier incarnation, the amateur detective – can we find other attempts at realism, psychological insight and conscious- rendering work? It seems to me that the sustained work of Edna O’Brien, spanning fifty years of exposing truths about of sex, power and violence has gone unacknowledged in the crime world.

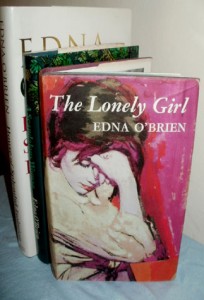

It will seem tantalizing or bizarre to some readers that we link such issues to the Irish writer Edna O’Brien. She has been categorised as the young author of the Country Girls trilogy and generally noted for these books because they were banned or burned in Eire and because in her personal life she left organised religion and motherhood behind when she left your country. But Edna was from the beginning a seeker after larger truths. Educated in a convent school and still a young woman of eighteen when she was clutched away from a chemist shop in Dublin and taken to London by a much older and more experienced man. She it seems to have gone along with it in the expectation of finding a better world, had two children in her relationship, then found another form of repression or restriction on her self-identity. Soon the relationship broke down and she found herself homeless. What had she to fall back on? Edna had immersed herself in the Irish writers of plays, short stories and novels from a young age. Her sources of inspiration were hard edged, tragedy-comedies with some humour and a search for release. She was soon accepted internationally by her peers as a contemporary voice speaking about her times, and specifically respected for her slant on her sex, age-group and country. Because of her reputation she could not be ignored in her country, the censorship and book burning began with her first novel, The Country Girls.

It will seem tantalizing or bizarre to some readers that we link such issues to the Irish writer Edna O’Brien. She has been categorised as the young author of the Country Girls trilogy and generally noted for these books because they were banned or burned in Eire and because in her personal life she left organised religion and motherhood behind when she left your country. But Edna was from the beginning a seeker after larger truths. Educated in a convent school and still a young woman of eighteen when she was clutched away from a chemist shop in Dublin and taken to London by a much older and more experienced man. She it seems to have gone along with it in the expectation of finding a better world, had two children in her relationship, then found another form of repression or restriction on her self-identity. Soon the relationship broke down and she found herself homeless. What had she to fall back on? Edna had immersed herself in the Irish writers of plays, short stories and novels from a young age. Her sources of inspiration were hard edged, tragedy-comedies with some humour and a search for release. She was soon accepted internationally by her peers as a contemporary voice speaking about her times, and specifically respected for her slant on her sex, age-group and country. Because of her reputation she could not be ignored in her country, the censorship and book burning began with her first novel, The Country Girls.

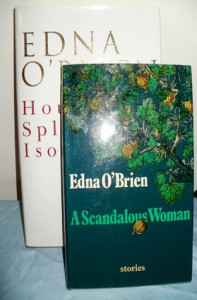

Certainly O’Brien’s work in the early years the stories were of awakening or rites of passage where her characters tried to reach beyond their circumstances and the possibilities where to be had. In the middle period that feeling becomes curtailed and stunted. A typical example of her treatment of social control and sexual domination is found in her the title story of A Scandalous Woman (1974). Eily is seduced, impregnated and abandoned by her lover; beaten, imprisoned and forcibly married off by her father; driven mad, institutionalized, drugged and then delivered back sane but with the spirit knocked out of her. This a description of a harsh, even brutal area of life. Her characters are caught in these situations with no real intervention from the outside world, and it leaves one with a feeling of the bonds of the past are deeply affecting them. The fearlessness of Baba in the early books has given way to the acceptance of Eli. How they survive and assume a dignity is crucial to the resolution of the story. In bringing out hidden or taboo topics such as self-abortion (A Pagan Place) O’Brien conveys the barbarity and the psychological torment that must have damaged one generation, next another. Her method of delivery is frequently the potent metaphor. This allows the reader and those in the narrative to take in what is going on without too much distress.

Certainly O’Brien’s work in the early years the stories were of awakening or rites of passage where her characters tried to reach beyond their circumstances and the possibilities where to be had. In the middle period that feeling becomes curtailed and stunted. A typical example of her treatment of social control and sexual domination is found in her the title story of A Scandalous Woman (1974). Eily is seduced, impregnated and abandoned by her lover; beaten, imprisoned and forcibly married off by her father; driven mad, institutionalized, drugged and then delivered back sane but with the spirit knocked out of her. This a description of a harsh, even brutal area of life. Her characters are caught in these situations with no real intervention from the outside world, and it leaves one with a feeling of the bonds of the past are deeply affecting them. The fearlessness of Baba in the early books has given way to the acceptance of Eli. How they survive and assume a dignity is crucial to the resolution of the story. In bringing out hidden or taboo topics such as self-abortion (A Pagan Place) O’Brien conveys the barbarity and the psychological torment that must have damaged one generation, next another. Her method of delivery is frequently the potent metaphor. This allows the reader and those in the narrative to take in what is going on without too much distress.

Her later work takes these themes and broadens them out to a wider social landscape. In House of Splendid Isolation (1994), her novel about a terrorist who goes on the run she raises questions about her country and its destiny that are powerful and cathartic. McGreevy, an I.R.A. terrorist known as the Beast has been betrayed and following escapades he moves into and takes over an ageing Catholic widow’s house. This is one drama – full of tragic events, political violence and menace. Another narrative gives us an account of Josie’s passion for the local priest. Josie is obsessed with him, she pursues him, and though the affair comes to nothing she suffers a brutal beating, and despised by the village. She works the two stories together through a minor character. What is going on here is individual lives written in blood by the story of Ireland. Everything is symbolic.

It was the first of several contemporary novels that took the rape victim of her early books but now pointed to a country that had lost its conscious, become in her view bereft of purity and spirituality; and the context of political antagonism and violence came to the fore.

O’Brien’s influence can be seen in the broader arts, through the television drama of the Country Girls (a Channel 4 production with Sam Neill), through twenty odd stage plays and the films such as The Girls with Green Eyes (with Rita Tushingham) and Zee and Co (with Elizabeth Taylor). But it is the writers that took on her legacy that interest me. Most certainly, Colum McCann the award winning post modern writer echoes her work. As do in another way the violence and social commentary in Tanya French, Ken Bruen and Stuart Neville. Without Edna O’Brien we can ask would we have authentic Irish crime writers today?

NB. You may be interested in seeing this revealing video interview with Edna O’Brien.

NB. You may be interested in seeing this revealing video interview with Edna O’Brien.