I have long been impressed with the crime and adventure thrillers of Lionel Davidson. When we came to publish Original Sins, the Crime Writers’ Association anthology edited by Martin Edwards, he asked if I would care to write a tribute essay on the achievements and contribution that Lionel had made. Here is the essay.

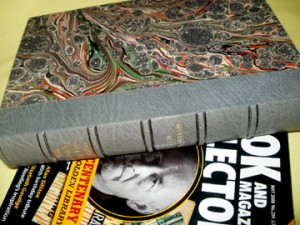

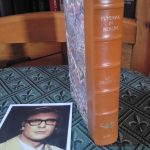

As a bookseller and publisher, I have been acquainted with Lionel Davidson through my career spanning more than two decades. I had sold collectible copies of his early books to customers and talked over why they were drawn to this particular author. Occasionally I wrote to Lionel to pass on pertinent comments and enquire about his next book. A subject on which he would pass over. Then about six years ago I suggested that we co-operate on a book about his work – an overview essay, a recorded interview and an annotated bibliography including his screenplays. He graciously accepted and the book (which also covered the work of Dick Francis) was published in 2006. [see picture below] What follows is a brief resume of his literary career followed by a more detailed look at his early development.

As a bookseller and publisher, I have been acquainted with Lionel Davidson through my career spanning more than two decades. I had sold collectible copies of his early books to customers and talked over why they were drawn to this particular author. Occasionally I wrote to Lionel to pass on pertinent comments and enquire about his next book. A subject on which he would pass over. Then about six years ago I suggested that we co-operate on a book about his work – an overview essay, a recorded interview and an annotated bibliography including his screenplays. He graciously accepted and the book (which also covered the work of Dick Francis) was published in 2006. [see picture below] What follows is a brief resume of his literary career followed by a more detailed look at his early development.

During the 60s Davidson was a fresh, energetic and talked-about writer. He published four very different, yet unrelated books that were equally widely read and praised at a critical time of change. New writers of popular fiction such as J G Ballard, Len Deighton and John Fowles, to name just three, were far less insular outlook than their predecessors, favoured experimentation and were buzzing with ideas. This freshness began to impact upon the field of crime and detection. For many crime fans, critics and writers Lionel Davidson was seen as a gifted and avant garde exponent of this 1960s new wave.

At the peak of his powers Davidson had options aplenty. Two of his mid 60s books had led him deeper into experiencing the Jewish past, with a kind of foreknowledge of connections to the wider present. Lionel himself felt the desire to be part of a larger purpose and looked to fulfil these ambitions when moving to Tel Aviv. It would be true to say that at the time his project was much larger than one would usually acknowledge for a writer. His efforts were deployed in shaping ideas through screenplays, films as well as writing novels about the country he loved. Cinematography was another of his passions – but the making of films and documentaries depended on so many pieces coming together and was a heavy burden – crafting the story as both producer as well as writer; sometimes clashing with authorities, and being distracted by Hollywood and its values. Inevitably it was a distraction, for Lionel preferred to follow his own heart.

Despite or because of the decidedly mixed blessings of his involvement with cinema, his stay in Israel did account for Smith’s Gazelle and The Sun Chemist. They captured in words some of the big themes of freedom and subservience connected to his Jewishness. Nonetheless, they addressed universal themes, and prophesied the future of Arab-Israeli relations. As a humanitarian he felt genuinely that through dialogue and understanding a lasting peace with Israel’s neighbours was obtainable, if only people were broad-minded enough to let go of the past. But by the end of the 70s he felt the need to move on; the stay had lasted it course; he later hinted that Israeli society was restraining, the hoped-for peace was still far away and he had the schooling of two boys to consider. But for all his time way he could not have made a better return than with his only London novel, The Chelsea Murders – a  book that poured scorn on the detective story yet was so deliciously funny that it was awarded the CWA Gold Dagger. It marked Davidson out as the only author so far to win the prestigious award three times.

book that poured scorn on the detective story yet was so deliciously funny that it was awarded the CWA Gold Dagger. It marked Davidson out as the only author so far to win the prestigious award three times.

Lionel Davidson was never forgotten by those that read him during his most productive golden period. His skill and exuberance as a master of adventure and mystery resumed with the Siberian adventure tale Kolymsky Heights, published in 1994. But there was no follow-up. It had taken many years in conception and three years to write. He continued to research and sketch out ambitious novels. But all his post Kolymsky work remained unpublished, novels re-worked, outlines sometimes derived from his 60s interests lay dormant and without a publishing contract. Yet at his peak he made helped the development of crime writing (although Lionel would never acknowledge this; he was excessively modest and preferred the idiom of “popular entertainments” as did Graham Greene). And like Greene, he was also drawn to more weighty stories, with twists and choices to be made. There were marvellous subtleties to savour. He liked by turns to shock and then enthral; he “shocked” in the sense coined to describe the physical dangers and nasty goings on in the early twentieth century thrillers or “shockers”; yet his books were also civilised, thoughtful and mature entertainments. He managed to engross the reader and provide escapism with a tender touch, a little compassion and hope for a better tomorrow.

* * *

It is not widely known that Lionel Davidson’s occupation before becoming a successful published author was as a journeyman through the writing, publishing and media world: gaining experience as a reporter and later as editor of features and fiction. Before that he’d travelled during the Second World War as a submarine wireless operator patrolling the Far East; his travels continued after the war to Europe as a freelance news reporter searching for topical material. Some time later his duties at John Bull magazine involved commissioning work from popular authors such as Agatha Christie and all the while he wrote short stories (published under several pen-names). As a respected investigative journalist he gathered and organised newsworthy material; interviewing such notables as the fallen politician Oswald Mosley and the equally reclusive and much travelled thriller writer Alistair McLean; these subjects allowed him in ‘behind the scenes’ and offered insight into quite different walks of life. This apprenticeship allowed him to hone the skills of relaying to the reader such delicate nuances as how to orchestrate form and content, bringing fiction and non-fiction into his chosen mould. He would later draw on this as a novelist, as well as his disposition to continue to learn a broad range of artistic and scientific subjects: but for Lionel Davidson, knowledge was not an end in itself or even a framework for stories. Grounded as he was in an early twentieth century sense of progress and inquiry, partly influenced through reading widely and showing a leaning to leftist progressive English free-thought, yet of course his religious affiliation and ancestry shaped his other, perhaps secondary cultural identity: the Yiddish yearning for life and close, supportive relationships. These two different inheritances in outlook, his gift for expressing them as one, and conveying them in beautifully constructed stories made him a special writer. He characters lived, they had weight to develop into believable people, people that lived lives that his readers wanted to know about.

Lionel Davidson’s admirers invariably have a high opinion of his books, but I have noticed a tendency to view him either as a mainstream humorous writer, almost in the tradition of Wodehouse – or more commonly, as a thriller and mystery writer loosely in the tradition of Buchan and Ambler. This takes no account of the distinctive, yet multifaceted national and cultural backgrounds that underscore his longer works, neither does it throw light on the books he found most satisfying to write, which were for his own children to help them have a good night’s sleep! Personally, I found merit and satisfaction in all of these different sides, but his work as a whole presents much more to admire: an ingenious blending of mystery and imagination together with an underlying optimism about the human spirit and human relationships.

One reader recalled that Davidson’s very first novel was a humorous spy spoof that moves from familiar leafy suburbia to Cold War Prague; all with the trappings of an elegant English comedy of mistaken identity. For him Night of Wenceslas lay perhaps in a long and still blossoming literary and stage comic tradition. Others regarded the style and cleverness of the narrative, together with the developing atmosphere of encirclement as pointing to the tradition of Ambler and Greene. Lionel was particularly pleased with the reception the book received when finally published; notably the Author’s Club award for best first novel and the CWA Gold Dagger. He thought because of the various hitches with acceptance and a long printer’s strike it would never come out! All agreed though, it was a world away from James Bond, in some way a comfortable and traditional form of escapism, offered with wit and panache.

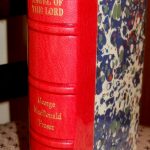

His next book, The Rose of Tibet is a favourite of mine and is the strangest and most endearing tale one is likely to find outside of the fantasy realm. By turns, funny, sexy, passionate, thrilling and exotic, it is a pleasant reminder of those books one reads as a  young person and never quite forgets such Hilton’s Lost Horizon, and Rider Haggard’s She and King Solomon’s Mines. There is action and misadventure, a near impossible journey of a journalist fellow and local guide trying to get into a forbidden Himalayan walled monastery high in the mountains. This is where he meets the rose of Tibet of the title: the woman with immortal eyes. The incidents of the second half of the story are both wondrous in terms of descriptive power and in giving the tale a memorable soul-defining edge. Encounters with wild bears and incursions by the Chinese military (this was the 50s) make the path all the most realistic and hazardous. Forced to rely on Nature for many months it is reminiscent of the wanderings found in the Jewish scriptures and a little of the adventures of Jack London. This outer journey for Charles and Mei-Hua mirrors an inner journey which they share with us.

young person and never quite forgets such Hilton’s Lost Horizon, and Rider Haggard’s She and King Solomon’s Mines. There is action and misadventure, a near impossible journey of a journalist fellow and local guide trying to get into a forbidden Himalayan walled monastery high in the mountains. This is where he meets the rose of Tibet of the title: the woman with immortal eyes. The incidents of the second half of the story are both wondrous in terms of descriptive power and in giving the tale a memorable soul-defining edge. Encounters with wild bears and incursions by the Chinese military (this was the 50s) make the path all the most realistic and hazardous. Forced to rely on Nature for many months it is reminiscent of the wanderings found in the Jewish scriptures and a little of the adventures of Jack London. This outer journey for Charles and Mei-Hua mirrors an inner journey which they share with us.

The intricate plot structure of his next book was also based on the notion of a journey. A Long Way to Shiloh introduces the reader to two journey narratives: firstly the prologue of past events nearly two thousand years ago about Imperial Rome and the sacking of the Temple in Jerusalem AD 70; then the current investigation in a journey all over Israel to seek out the whereabouts of the sacred treasure from the aforementioned Temple. The dialogue and convivial atmosphere is a delight. Then critic Anthony Price (a CWA Gold Dagger winner himself) was a member of the CWA award panel. He told me how impressed he was with the way Davidson had made the historical background an integral part of the plot.

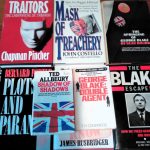

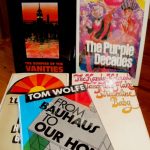

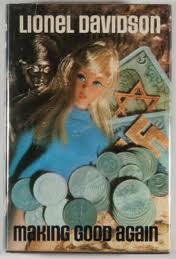

For his fourth novel, Making Good Again its author moved from Gollancz to Cape. Lionel was following a similar path as Kingsley Amis and J G Ballard who had made the move a few years earlier. Cape was one of the most respected publishing houses and also the home of Fleming and Deighton. Making Good was a book that addressed the vexed question of restitution for missing Jews. Full of pathos and humour it follows the investigation as a British lawyer delves ever deeper into the psyche of the German and Jewish characters. The novel builds into a clever, stylish book. A book that again takes one on a journey, with both emotional power and the ability to stretch ones intellectual preconceptions. Cape went on to publish all of Lionel’s children’s books and his remaining novels in attractive jackets. All, that is, except his last Kolmysky Heights.

For his fourth novel, Making Good Again its author moved from Gollancz to Cape. Lionel was following a similar path as Kingsley Amis and J G Ballard who had made the move a few years earlier. Cape was one of the most respected publishing houses and also the home of Fleming and Deighton. Making Good was a book that addressed the vexed question of restitution for missing Jews. Full of pathos and humour it follows the investigation as a British lawyer delves ever deeper into the psyche of the German and Jewish characters. The novel builds into a clever, stylish book. A book that again takes one on a journey, with both emotional power and the ability to stretch ones intellectual preconceptions. Cape went on to publish all of Lionel’s children’s books and his remaining novels in attractive jackets. All, that is, except his last Kolmysky Heights.

Lionel Davidson was a writer with a dizzying talent. His novels are interlaced with clever, cross the piece mixtures of realism and escapism. In the long run, although he did not write detective stories and psychological thrillers he became a moving force for opening up the crime fiction genre to other influences. He was above all a witty and dazzling entertainer, whose work deserves to be celebrated – and, above all, read and enjoyed.

Michael Johnson 2010

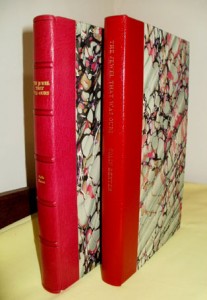

PS. Lionel Davidson is one of the two feature authors in our tribute book, Masters of Crime: Lionel Davidson and Dick Francis. It is a cerebration of them as writers and of the development of the adventure story; also included is an annotated bibliography and an interview with Lionel by Michael Hartland. The book is available as a trade paperback and also a a leather bound signed limited.